My goal for 2024 is to implement a simple programming language that compiles to WebAssembly and that I can use to solve at least one Advent of Code problem. In my previous post I explained how I arrived at that goal.

This post lays down a rationale for choosing Rust as the implementation language and how I set up the project.

Language choice

Most general-purpose programming languages can be used to implement a compiler. So from a language perspective, it does not matter, whether I choose Haskell, Kotlin, Java, JavaScript, TypeScript, Go, C, Rust or Zig1. However, there are a few features I would love to have without too much hassle.

It should be possible and simple to build a static binary for a command line interface (cli). It should also be possible to compile the compiler to WebAssembly so that it can be used in the browser or other languages, that support running WebAssembly programs. The language should have good tooling (IDE, LSP, formatter, package manager) because that just makes development much smoother and more fun.

Out of the mentioned languages, I don’t know C and Zig very much. Since this is a toy project, I could use them for the learning experience, but I fear that I will shoot myself in the foot too often because I never really had to think about memory management in the past.

Java, Kotlin, JS/TS are my daily drivers which makes them boring to use. Also in my experience, none of the CLI libraries are on par with a library like clap in Rust and a static binary might be possible with GraalVM and Deno/Bun, but that feels like complecting everything. Kotlin can be compiled to WebAssembly but this feature is in the early stages and requires the GC propsal, which is being implemented in browsers as far as I know, but not fully supported.

Haskell has a brilliant ecosystem for writing compilers and a good library for writing clis but compiling Haskell to WebAssembly is still in the early stages and also requires the GC proposal. Additionally, I never know what package manager to use (Stack, Cabal or both?) and in the past building static binaries always failed on me with some arcane compilation errors because of a missing shared library. I just want this to work and it might be better now, but I am not interested in trying it out again at the moment.

That leaves Rust and Go. Go ticks most boxes and is a language where the lack of abstraction compels me to write the code required to get things done, but its lack of sum types2 is a nonstarter for me. Especially when talking about compiler development. I know there are compilers written in Go, I mean the Go compiler itself is, but not having sum types in this case feels to me like not having Vim keybindings in an editor. As for WebAssembly, I believe Go can be compiled into it.

Rust on the other hand has the best CLI library of any programming language I know, especially of languages with a type system, can be compiled to WebAssembly and building a static binary with musl more or less just works. Additionally, Rust has a good ecosystem of libraries for writing parsers3, although I don’t plan to use any of them and is integrated with the WebAssembly ecosystem.

I believe you can do all of what I want to do with any of the other languages I mentioned here, but I feel this particular combination of features is tied together the best by Rust. Also, I just like the language and want to learn it more. I know it a little and hope that by using it more, the problems I sometimes have with lifetimes will get easier.

Setup

Rust has a package manager called cargo, which makes creating

a new package, called crate in Rust simple. For example, the

following command creates a binary crate.

$ cargo new waspHowever, as mentioned before, I would like to compile this program to a static binary and to WebAssembly. To keep these different concerns separate, there will be three crates as part of the project and one TypeScript npm module.

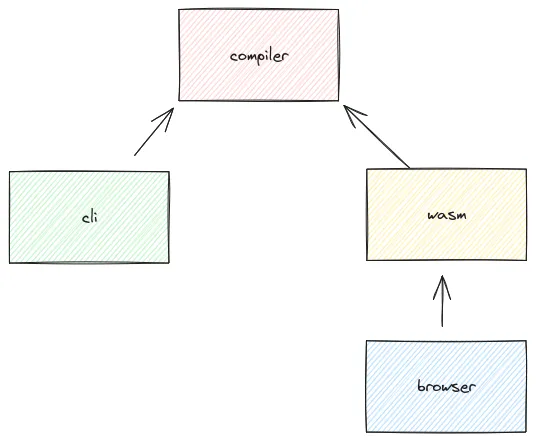

compilercontains the actual compiler. Ideally, the compiler is just a function, that I can call with a string of source code and that returns either a set of errors or a WebAssembly module.clicontains a command line interface for invoking the compiler from the command line.wasmuses wasm-bindgen and wasm-pack to compile Rust code to WebAssembly. wasm-bindgen is a tool to create high-level bindings so that Rust can call JS and vice-versa. wasm-pack is used to bundle the WebAssembly code so that it can be consumed from the web or a package manager.browseruses the WebAssembly output to use functions from thecompilerin the browser.

Here is a quick visualization of the dependencies of these crates/packages.

To make this work, Cargo provides workspaces. That means creating a crate works a bit differently.

$ mkdir wasp && cd wasp

$ cargo new compiler --lib

$ cargo new cli

$ cargo new wasm --libIn the wasp directory we can add a Cargo.toml with the following

content:

[workspace]

members = [

"compiler",

"cli",

"browser",

]Running cargo build in the root directory should now build all

crates.

CLI

To use the compiler crate in another crate, it can be added

in the [dependencies] section of a Cargo.toml. For example for the

cli crate:

[package]

name = "wasp"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2021"

[dependencies]

compiler = { path = "../compiler" }Now the add function in the compiler library, that was generated

by cargo during cargo new, can be used in the cli crate.

// src/main.rs

fn main() {

println!("{}", compiler::add(5, 6));

}Running this with cargo run cli should print 11.

WebAssembly

Setting up the wasm crate is more involved. First

wasm-pack and wasm-bindgen have to be

installed.

$ rustup component add wasm-bindgen

$ cargo install wasm-packThere are several examples in the documentation for these two tools, I

used the Cargo.toml from the WebAssembly starter example.

[package]

name = "browser"

version = "0.1.0"

edition = "2021"

[lib]

crate-type = ["cdylib", "rlib"]

[features]

default = ["console_error_panic_hook"]

[dependencies]

wasm-bindgen = "0.2.84"

compiler = { path = "../compiler" }

# The `console_error_panic_hook` crate provides better debugging of panics by

# logging them with `console.error`. This is great for development, but requires

# all the `std::fmt` and `std::panicking` infrastructure, so isn't great for

# code size when deploying.

console_error_panic_hook = { version = "0.1.7", optional = true }

[dev-dependencies]

wasm-bindgen-test = "0.3.34"

[profile.release]

# Tell `rustc` to optimize for small code size.

opt-level = "s"With this it is possible to build a .wasm file, that can be used for

example in vite. To try this out add the following to

wasm/src/lib.rs file:

use wasm_bindgen::prelude::wasm_bindgen;

#[wasm_bindgen]

pub fn add(a: usize, b: usize) -> usize {

compiler::add(a, b)

}Build it:

$ cd wasm && wasm-pack build --target bundler

$ cd ../Then create a vite project and configure vite-plugin-wasm. There are other plugins that can be used, but they seem to be comparatively old and I haven’t tried them.

$ npm create vite@latest browser

$ cd browser

$ npm install

$ npm install --save-dev vite-plugin-wasm vite-plugin-top-level-awaitConfigure the build in the vite.config.ts:

import { defineConfig } from 'vite'

import react from '@vitejs/plugin-react'

import wasm from 'vite-plugin-wasm';

import topLevelAwait from 'vite-plugin-top-level-await';

// https://vitejs.dev/config/

export default defineConfig({

plugins: [react(), wasm(), topLevelAwait()],

})And use it.

import { add } from '../wasm/pkg/browser_bg.wasm';

console.log(add(5, 6));Conclusion

This post is quite long and explained my rationale for choosing Rust and how I setup the project. You can see all the code here. I hope this keeps working, but there are probably some gotchas in the near future, especially concerning the WebAssembly integration.

Next week will take a look at the language I would like to write or maybe I am starting off with a lexer.

Happy week!

Footnotes

-

Of course there are other languages (Clojure, Racket, Elixir, C#, F#, C++), but I don’t feel like I know enough about them to assess whether they would annoy me. ↩

-

Sum types are essentially enums which can have instance variables for a variant. ↩

-

I love PEST, it’s just so much fun to define grammars with it. Highly recommended! ↩